Archive

Setting up XMPP BOSH server

This tutorial explains how to setup/troubleshoot XMPP server with BOSH. I’m not getting into what is XMPP and what is it good for. The first two paragraphs are theoretical. XMPP is stateful protocol in a client-server model. If web application needs to work with XMPP a few problems arise. Modern browsers don’t support XMPP natively, so all XMPP traffic must be handled by program running inside the browser (JavaScript/Flash etc…). The first problem is that HTTP is a stateless protocol, meaning each HTTP request isn’t related with any other request. However this problem can be addressed by applicative means for example by using cookies/post data.

The second problem is the unidirectional nature of HTTP: only the client sends requests and the server can only respond. The server’s inability to push data makes it unnatural to implement XMPP over HTTP. The problem is eliminated if client program can make direct TCP requests (thus eliminating the need of HTTP). However, if we want to address the problem within HTTP domain (for example because Javascript can only forge HTTP requests) there are two possible solutions, both require “middleware” to bridge between HTTP and XMPP. The solutions are “polling” (repeatedly sending HTTP requests asking “is there new data for me”) and “long polling”, aka BOSH. The idea behind BOSH is exploitation of the fact that the server doesn’t have to respond as soon as he gets request. The response is delayed until the server has data for the client and then it is sent as response. As soon as the client gets it he makes a new request (even if he has nothing to send) and so forth.

BOSH is much more efficient, from server load’s point of view and traffic-wise. In this tutorial I set up Openfire XMPP server (which also provides the BOSH functionality) with JSJaC library as client, using Apache as web server on Ubuntu 10.04. Openfire has Debian package and as such, installation is fairly easy. Just download the package and install. After installation browse to port 9090 on the machine it was installed on, and from there it’s web-driven easy setup. If you choose to use MySQL as Openfire’s DB make sure to create dedicated database before (mysqladmin create).

After initial setup, I wasn’t able to login with the “admin” user. This post solved my problem, openfire.xml is located at /etc/openfire (if you installed from package), you will need root privileges to edit it and then restart Openfire (sudo /etc/init.d/openfire restart). Other than that everything worked fine. Openfire server (as well as all major XMPP servers) provides the BOSH functionality, aka “HTTP Binding” aka “Connection Manager”. By default it listens on port 7070, with “/http-bind/” (the trailing slash is important).

To make sure it works (this is the part I couldn’t find anywhere, that’s why it took me long time to resolve all problems) I used “curl”, very handy tool (sudo apt-get install curl). To test the “BOSH server”:

# curl -d “<body rid=’123456′ xmlns:xmpp=’urn:xmpp:xbosh’ />” http://localhost:7070/http-bind/

Switch “localhost” with your server name, notice the trailing slash. Expected result should look like:

<body xmlns="http://jabber.org/protocol/httpbind" xmlns:stream="http://etherx.jabber.org/streams" authid="2b10da3b" sid="2b10da3b" secure="true" requests="2" inactivity="30" polling="5" wait="60"><stream:features><mechanisms xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:xmpp-sasl"><mechanism>DIGEST-MD5</mechanism><mechanism>PLAIN</mechanism><mechanism>ANONYMOUS</mechanism><mechanism>CRAM-MD5</mechanism></mechanisms><compression xmlns="http://jabber.org/features/compress"><method>zlib</method></compression><bind xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:xmpp-bind"/><session xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:xmpp-session"/></stream:features></body>

Once verified, we can continue with the next step. Since the client is Javascript based, all Javascript restrictions enforced by the browser applies. One of these restrictions is “same origin policy“. It means that Javascript can only send HTTP requests to the domain (and port) it was loaded from and since it is served on HTTP (port 80) it can’t make requests to port 7070. Solution: Javascript client will make requests to the same domain and port. The requests will be forwarded locally to port 7070 by Apache. I guess you can use the same method to forward even to a different server but I didn’t try. I configured forwarding following this post but there is probably more than one way to do it.

Add to /etc/apache2/httpd.conf the following lines (root privileges needed):

LoadModule proxy_module /usr/lib/apache2/modules/mod_proxy.so

LoadModule proxy_http_module /usr/lib/apache2/modules/mod_proxy_http.so

Then, add to /etc/apache2/apache2.conf the following lines (root privileges needed):

ProxyRequests Off

ProxyPass /http-bind http://localhost:7070/http-bind/

ProxyPassReverse /http-bind http://localhost:7070/http-bind/

ProxyPass /http-binds http://localhost:7443/http-bind/

ProxyPassReverse /http-binds http://localhost:7443/http-bind/

Now restart the Apache (sudo /etc/init.d/apache2 restart) and make sure it starts properly. To verify the forwarding works, use the same curl method, this time as request to the Apache:

# curl -d “<body rid=’123456′ xmlns:xmpp=’urn:xmpp:xbosh’ />” http://localhost/http-bind

The result should be the same as before. If it doesn’t work there is problem with the forwarding. Once it is working, server side is ready. On the client (in my case JSJaC), you should specify to use BOSH/HTTP Bind “backend” (as opposed to “polling”). For “http bind” url just use “/http-bind” and everything should work. Notice that if you open the client locally on your desktop (not served by the Apache) it won’t work because of the “same origin policy” mentioned before.

I hope you find this tutorial useful, it sure could have helped me… 🙂

Faking the Green Robot – Part 2

It has been long time since Part 1, but I’ve been busy with other stuff. In the previous part, I started analyzing how “Green Robot” feature can be faked, or more precisely, how Android is identified by google talk servers. Last thing I found out was that Android’s talk application securely connects to gtalk servers. I performed SSL man in the middle attack as described in this post. I couldn’t find weakness in Android’s SSL implementation, so I had to modify it to accept my fake certificate. How did I do that ?

My first guess was to change something inside Talk.apk or gtalkservice.apk to either disable the check, or get it’s private key. If you are a software developer you’d probably think I must have the original source files for that, but the truth is I don’t. Quick inspection of “apk” files showed that it’s actually gzip archive, that contains some xml files and the executable binary, “dex” file. Another format I’ve never heard of. What I wanted to do next is something called disassembly process. It means turning binary machine code into something more readable by humans.

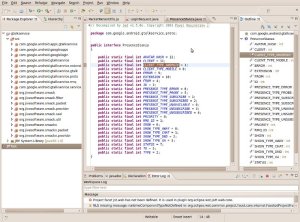

Unfortunately, my favorite disassembler doesn’t understand dex files, so I googled for help and found two candidates: “dedexer” and “dex2jar“. The first decompiles into “assembly like format” while the second converts to Java jar, which can be later disassembled into java source files. So, dex2jar was an obvious pick. I then disassembled the jar file with JAD (JAva Decompiler). Although, it wasn’t fully disassembled, it was enough to get around.

Unfortunately, my favorite disassembler doesn’t understand dex files, so I googled for help and found two candidates: “dedexer” and “dex2jar“. The first decompiles into “assembly like format” while the second converts to Java jar, which can be later disassembled into java source files. So, dex2jar was an obvious pick. I then disassembled the jar file with JAD (JAva Decompiler). Although, it wasn’t fully disassembled, it was enough to get around.

After brief inspection of “gtalkservice” and “Talk”, I realized the SSL authentication mechanism is not implemented by neither of them, it’s implemented by Android operating system. So, there must be a place that holds the trusted certificates. I only need to find it and add my fake certificate (served by the man in the middle server). I scanned the operating system files for suspicious files (remember ? we extracted system.img with unyaffs so we have access to these files). Umm… I wonder what /etc/security/cacerts.bks is used for… what are the odds it holds all trusted Certificate Authorities Certificates ?

To modify this file we need some sort of editor for bks files. Portecle would be good choice. The bks file is password protected but the password can be obtained here, along with instructions how to extract it from live android operating system, modify it, and push it back to android. None of the instructions worked for me, but the password was correct. Portecle’s usage as well as cacerts.bks file structure is pretty intuitive.

Once cacerts.bks contains our new certificate we need to push it back into the system.img file the emulator use. I thought it’s trivial task but it took me much more time than I expected, much more than actually needed. If you follow google results, you would either try to push the file into live android system with “adb push”, but it doesn’t survive reboot (and you must reboot if you want the new file to be used) or you follow one of the many different forums posts about kernel recompiling, using mtd pseudo devices, etc…

All you really need to do is download YAFFS2 source, go to “utils” directory, and run “make”. When compilation is done, you’ll get utility called “mkyaffs2image” which is exactly what we need. It converts a directory (with it’s files and subdirectories) into YAFFS2 image. We just need to rebuild YAFFS2 image from the extracted system.img direcrtory (with modified cacerts.bks file in it). After it’s done, rename output file to system.img and boot the emulator with it. It works seamlessly.

All you really need to do is download YAFFS2 source, go to “utils” directory, and run “make”. When compilation is done, you’ll get utility called “mkyaffs2image” which is exactly what we need. It converts a directory (with it’s files and subdirectories) into YAFFS2 image. We just need to rebuild YAFFS2 image from the extracted system.img direcrtory (with modified cacerts.bks file in it). After it’s done, rename output file to system.img and boot the emulator with it. It works seamlessly.

So now I got all communications decrypted with wireshark. I expected to find google talk’s offical protocol, XMPP, as specified here but I didn’t. What I got seemed like some sort of object serialization. Some of the strings looked familiar from XMPP protocol, some were not. I checked gtalkservice sources again, to understand the serialization process. I couldn’t figure it out completely but I got some ideas, such as the first byte of packet represents it’s type as defined in MobileProtoBufStreamConfiguration.java, the second byte is how many bytes left in the packet, string always follows it’s length (in hexadecimal), etc…

I figured out enough to come to these conclusion: port 5228 is not only used for google talk. It’s for other google services as well. The protocol is some “private” extension of XMPP or pure XML, as the smack sources (from gtalkservice) were clearly modified to handle login requests. All objects are serialized. I suspect the android identification is based on the login request ( <login-request … deviceId= …> ).

Therefor, my plan for extending existing gtalk client with some additional XMPP tags won’t work, because the whole login procedure is apparently different. That’s the end of this adventure for me. Of course, I might be wrong or completely missing something, but for what it worths, it was fun and I got quite far, didn’t I ?

However, this is the end only for me. For you, there still might be a chance. If I got it right, when client receives “presence” messages, which are part of the XMPP (those are the messages sent to notify someone became online for example), one of the fields is client type, as specified in PresenceStanza.java. Although it interprets only received messages (again, if I got it right), the XMPP protocol also defines how to send presence messages to the server. Maybe this type of messages can be used to trick the server…